Australia’s favourite oysters will be harder to find on menus this season!

Once plentiful, oysters may be becoming a rare delicacy due to a warming climate and extreme weather events.

The combination of bushfires and heavy rain have led to the water being polluted, and the floods to cause oysters to be contaminated and ruin. The likelihood of diseases in oysters has increased, while the warming climate has brought more pests and savage weather to oyster reefs. Oysters indicate the health of the waterways and can be one of the slowest creatures to recover after disease and flooding events.

Combining this with Covid-19 lockdowns, many oyster farmers, especially in NSW, have had to close or stop harvesting as their oyster supplies have been devastated.

1. Why are Oysters harder to find?

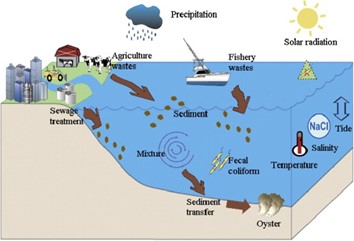

Severe rain events and floods have impacted harvests in major production rivers. This is due to too much rainwater washing into estuaries, raising the freshwater levels beyond what some oysters can survive.

With one rain event after another the ground has been so wet that no more water can soak into the ground consequently the rainwater just goes back into the estuaries.

As oyster’s natural habitat is the sea, they need the salt, and when too much rainwater is added to the estuaries and rivers, then the salinity is altered, and rivers go fresh for too long. This has led oyster farmers to see high mortality levels. Additionally, oysters have trouble building their shells in more acidic water which again can be related to drought or floods.

Warmer temperatures due to climate change raise the oyster’s metabolic rate, which in turn raises its oxygen and food intake requirements. The health of an oyster reef is critical for the oyster’s survival.

2. Which types of oysters are grown in Australia?

There are three different types of oysters grown in Australia.

- Rock Oysters are deep, rich, and sweet in flavour with a finishing mineral taste. They are best eaten from September to March and Spring to Winter. The Sydney Rock Oyster is the most popular.

They are found along the East coast of Australia and like all oysters they have flavour characteristics which reflect the waterers where it was raised that varies from brinier if farmed closer to the mouth of an estuary where salinity is high to slightly sweeter if there is lots of sea grass and seaweed.

- Pacific Oysters are like Rock Oysters but tend to be not as sweet and a little briny. They have a fresh, crisp, and salty flavour. They are best eaten April to September.

They are farmed in cooler areas like Tasmania and South Australia but can be found in New South Wales and Queensland. Pacific Oysters are usually larger and plumper than Rock Oysters with a milder, creamier taste.

- Angasi Oysters are full bodied, finely textured and rich in flavour. Best eaten from May to November.

Native to Australia they are closely related to Belon oysters from France. Only a few producers farm them, so they are rare. They are a large ‘flat’ oyster but are hard to open as the hinge will not pop easily.

3. What are oysters?

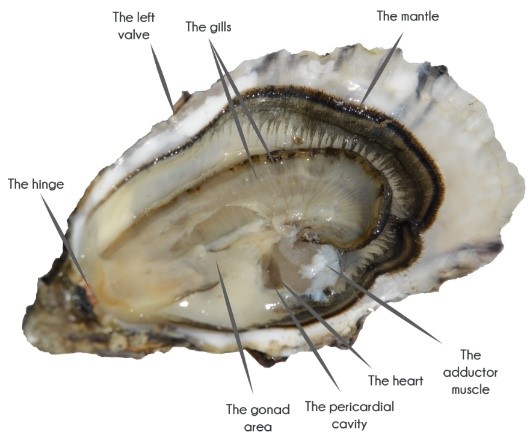

Oysters are soft bodied animals that protect themselves with a shell. As bivalve molluscs they have two sells which are connected by a small hinge. This allows the oyster to open their shells to intake food and expel waste. They can close their shells if threatened by predators.

Oysters are animals that eat algae and other food particles that are usually taken into their gills. Oysters are known for cleaning the water of the oceans and can process up to 10 litres of water an hour.

Like other molluscs, oysters have a simple biological system. They can be found in salt water and water which is less saline than true marine environments. These “brackish’ areas are transitional areas between fresh and marine waters like an estuary which is part of a river that meets the sea.

They are seen to be economically valuable animals because they can provide a source of food and pearls. Many other animals are also fond of oysters due to their flavourful, protein rich flesh.

4. What diseases do oysters carry?

- Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection can be acquired as result of eating raw or undercooked oysters. Vibrio is a bacterium that naturally occurs in warmer, saltwater coastal environments. Vibriosis is and intestinal disease.

When ingested, vibrio bacteria can cause gastroenteritis, giving abdominal cramping, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fever, and chills. The symptoms occur withing 24 hours of eating an infected oyster and last about 3 days.

- Norovirus infection is acquired by eating oysters contaminated by sewage in water before they are harvested. The contaminated sewage has vomit or stools from infected people. Noroviruses are very contagious and can easily spread from person to person.

Norovirus causes an acute illness with similar symptoms to food poisoning. The illness generally lasts 1-2 days although some people may be ill or feel the effects for up to 6 days. After the period of illness, the body gradually gets rid of the entire virus.

- Hepatitis A can be acquired from oysters that on feeding has filtered water that has been contaminated with a stool containing hepatitis A virus. The virus causes a person’s liver to become inflamed.

Symptoms include fever and joint pain. Vaccines are available to prevent this condition.

5. What causes QX disease in Sydney Rock oysters?

The title ‘QX’ which stands for ‘Queensland Unknown’ was given to the disease in 1976 before scientists discovered the cause was due to parasites. This protozoan parasite- Marteilia sydneyi, leads to Marteiliosis, a disease that infects the digestive system of Sydney Rock oysters.

QX is a seasonally occurring disease and causes impacts in some of the estuaries in NSW. Infections usually occur between January and April each year. It is only known to infect bivalves, such as oysters, mussels, and pipis, and does not have any impact on human health.

This year oyster farmers around Port Stephens in NSW have had their entire oyster crop ruined when their oysters were ravaged with QX disease, leaving piles of oyster ‘graveyards’.

Along with the battle of floods affecting supplies, little or no stock of Sydney Rock oyster will be available out of Port Stephens as pretty much as so many farmers have lost 100% of their Sydney Rock oyster crops. Many have turned to Pacific oysters, but they have had unexplained mortality too, which will affect Christmas stock.

6. What are the risks to oysters with increased climate change?

Sea-level are rising because of climate change, this is increasing the likelihood of the intertidal reefs being submerged, which are the rocky areas of the coastline extending up to the high tide mark. The submerging of these oyster reefs may increase oyster mortality. It could also change specific ecosystem services that the oyster reefs provide. For instance, it could reduce the ability of oyster reefs to decrease wave energy and prevent erosion.

The other more ominous threat of climate change is that major predators of oysters such as fish, crabs and snails can get to the oysters more easily when the oyster reef is damaged. These predators can then hunt and kill oysters more easily.

Environmental factors such as changes in salinity or temperature will affect oysters but can increase the mortality of the marine snails as oyster predators. The increase in the number of predators increasing the oyster number decline.

7. How does pollution affect pearl formation in oysters?

Pearl cultivation is big business in Australia, with much of it taking place in the oceans. But the oceans are becoming more acidic by the increased amounts of carbon dioxide in the air being absorbed.

Research has found that pearl oysters produce weaker shells in acidic oceans. This in turn decreases their chances of survival and will directly affect oysters and their pearl formation. In addition to acidity, rising water temperatures can affect the oyster’s health and pearl production. However, some researchers have concluded that warmer oceans could buffer the oysters from increasingly acidic seawater.

8. How do you know if an oyster is good to eat or has gone bad?

To tell if an oyster is good to eat, the bottom of shell of the oyster should be inspected to see if it has been broken or has damaged areas. The colour of the shell should be a glossy white and with even a few pink or grey streaks, it is still safe to eat.

The oyster shell should be tightly closed and if the shell is open it means it is weak or dead and consequently may harbour bacteria. Be wary if the oyster is dry as this means it is weak, injured or dying. The oyster may also have gone bad if it smells or tastes differently from the rest of the harvest. Contaminated oysters are generally grey, brown, black, or pink in colour.

Good oysters should smell like ‘ocean air’ and should be as cold as the ice they are stored in. Highest quality oysters are never dried out or wrinkled.

9. Do you eat oysters raw or cooked?

Never undercooked oysters and only eat fully cooked oysters at restaurants. Although oysters are served with hot sauce or lemon juice, this does not kill lemon juice.

Once oysters are taken out of their shell, they can be served raw, baked, steamed, boiled, or grilled. As oysters do not take long to cook, they will go tough if cooked for too long. Eating too many oysters in one sitting can cause nausea, tummy upsets and diarrhea. To be cautious eating 3-6 oysters is often advised.

Oysters will keep up to 7 days in the fridge once opened but their flavour will get tainted as they absorb any strong flavours from other items in the fridge.

The chances of finding a natural pearl in an oyster at a restaurant are very slim, but still possible!

10. How do you eat oysters?

Take a small fork provided and move the oyster around to make sure the oyster is detached from the shell. Oysters are finger food, so they can be picked up and slurped from the wide end of the shell by tipping slightly. The fish and all the liquid that comes with it need to be swallowed too.

It a common misdemeanour that oysters as supposed to allowed to slide down your throat without biting it but if you do not chew the oyster once or twice you will not get the full flavour.

Etiquette says that the empty shell should be laid back on the platter face down so that the server knows you have finished.

Various accompaniments can be added like lemon, cocktail sauce. And a red wine vinegar mix with shallots called mignonette sauce, which can be sprinkled on top of the oyster using the tiny fork.

The taste of the oyster can be described as copper, briny, metallic, tinny, buttery, melon, sweet, salty. Texture words include, soft, firm chewy.