As plastic accumulation escalates scientists across the world are trying to find an environmentally accepted solution to naturally dispose of plastics.

Australian scientists in Queensland have found that the Darkling beetle larvae, the so-called superworms, can degrade plastics and hope to find the key to solving the plastic problem on a large scale.

These superworms are breaking down and consuming plastic. This could offer a significant advancement in plastic recycling and put humans on the right track to breaking down plastic on a large scale.

1. What are superworms?

This insect is wrongly called a ‘superworm’ as it is not a worm at all! It is in fact a plump little bug in its larval stage of a type of darkling beetle, Zophobas Morio.

A superworm looks like an elongated, slippery caterpillar. They are the length of a paperclip and around five times larger than a mealworm when the girth and the length are considered. The difference in size comes mostly from the superworm having more chitin, a major constituent of the exoskeleton than mealworms do. This gives a higher concentration of calcium, fibre, and fat but less meat.

It is frequently used as food for pet reptiles

2. How do superworms digest plastic?

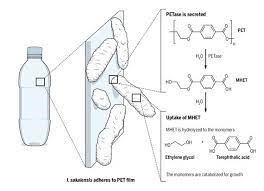

Researchers have identified bacteria in the gut of superworms which produces, an enzyme called serine hydrolase. This enzyme appears to be responsible for most of the biodegradation of plastic. The hope is that someday this enzyme or the bacteria that produce it in the superworm can be used to break down the accumulation of polystyrene waste.

The enzyme can break down polystyrene, commonly known as Styrofoam, into its component molecules. As the carbon is consumed it can be used as both a carbon and energy source.

Researchers have found that after eating the plastic, the superworms can gain weight on an exclusive diet of polystyrene and grow.

3. Can researchers in Brisbane offer hope for recycling using superworms?

The hope that these polystyrene-munching beetle larvae can gain weight and survive solely on polystyrene has been a boost to the research on ways bacteria and other organisms can consume plastic materials.

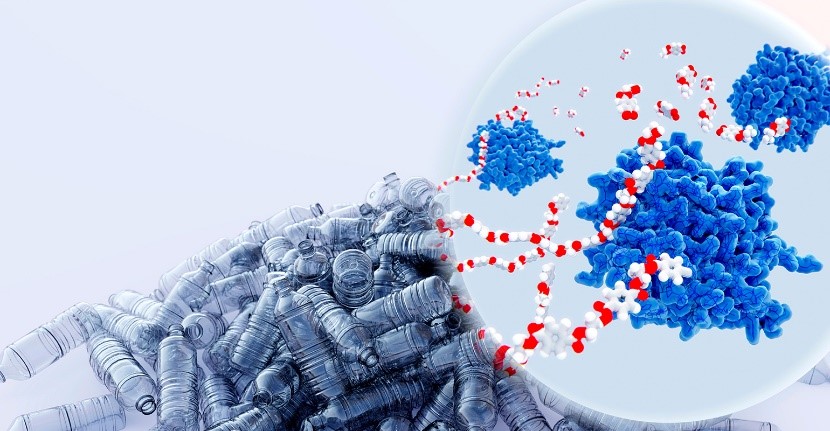

Researchers from the University of Queensland in Brisbane are now studying the enzymes that allow the superworm to digest. This research hopes to pave the way for the technology to degrade and recycle plastic on a large scale.

Many researchers in this field including the ones from Australia are looking to find a way to transform the findings into commercial products. The challenge is to guarantee that the superworms can digest plastics at large levels at a very quick and efficient rate.

Alternatively, if the gut enzymes which break the plastic down could be cultivated, then superworms could be left out of the equation.

A natural industrial way to dispose of and recycle this polymer trash in an environmentally friendly way would be what the world is waiting for!

4. Why is Polystyrene/Styrofoam a big problem?

Polystryrene like all plastics, does is not biodegradable and is especially difficult to get rid of. The material is dense and takes up a lot of space. This makes it costly to store at waste management facilities.

The cups, plates and other everyday materials made from polystyrene are also often contaminated with food and drink making it even harder to recycle. As it fills landfills it can often take 500 years to break down and decompose.

Discarded polystyrene can account for as much as 30% of landfill space worldwide.

Even with the present research it is estimated that getting a new superworm product off the ground for waste managers to use would be 5-10 years in the making.

5. What previous research has been carried out in this field?

Previously, Stanford University researchers 2015 announced that the smaller mealworm can survive on polystyrene. In 2016 Japanese scientists found bacteria that could eat plastic bottles. This was followed by researchers from the University of Texas finding an enzyme that could digest polyethylene terephthalate a plastic found in food containers, liquid containers, and clothes.

Scientists across the world are striving to find bacteria and other living organisms that naturally get rid of plastic waste. The enzymes they produce have the potential to supercharge recycling on a large scale. It would allow major industries to reduce their environmental impact by recovering and reusing plastics at a molecular level.

6. How are Australian scientists carrying out their research?

Researchers in Australia have discovered that superworms can get energy from polystyrene and go through their entire lifecycle without appearing unharmed.

This research is being led by Christian Rinke, a senior lecturer at the University of Queensland and senior author of the study.

To do this initially the researchers fed three separate groups of superworms different diets for 3 weeks.

One group were given nothing to eat, one group were fed bran flakes and the third shredded their way through plastic before digesting it by using the bacteria in their gut.

Their next steps now involved categorising those enzymes in more detail so that this enzyme combination could also be created to help plastic degrade.

The team found several enzymes in the superworm’s gut can degrade polystyrene and styrene

The hope is that once these enzyme cocktails are created, they can make them work faster and incentivise more recycling.

7. Are the superworms that are feed on plastic harmed?

It appears that the superworms fed on polystyrene have ‘guts of steel!’ However, as they grow and survive, they only have minimal weight gain. This results in a lower pupation rate than the other control group fed on bran.

Yet these polystyrene decomposers were all able to complete their life cycle to pupae and the final fully developed adult stage of the beetle.

8. Why is it so hard to decompose plastic?

Plastic is made from a product of oil, using heat and a catalyst to change the propylene into polypropylene, a substance not found in nature.

As these man-made plastics are not found in nature, then normal decomposing organisms cannot decompose the material, so it will not degrade like other plant and animal waste.

Plastics cannot be safely burnt as the fumes are carcinogenic. They pollute the environment at a staggering rate as this indestructible, non-decomposable volume builds up.

Plastics are killing wildlife when they mistake the product for food. When swallowed, they stick in the body until the animal or bird dies of starvation.

Many creatures get tied up and trapped by plastic waste particularly in the immense build-up in our oceans

There are some plastics that are processed to avoid the strong carbon bonds formed in the heating process, but they will not last as long as the mainstream plastics and will start to break down much sooner.

9. How fast do superworms breed?

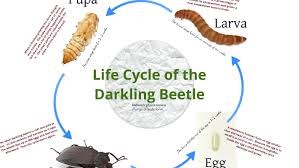

Superworms are larvae of the Darkling Beetle

Superworms have 4 stages in their life cycle: egg, larva, pupae, and beetle. The beetles are fertile their entire life and live about 5 months. A female superworm Beetle can lay up to 500 eggs in her lifetime. It takes 7-10 days for the eggs to hatch, and then very small white larvae will be visible.

These superworm larvae can grow to 50-60mm long and take up to 4-6 months. This is the plastic munching stage!

If allowed to remain with other superworms, they will live for 6 months to a year. Only when isolated from other superworms will their bodies begin to pupate.

At this size, they will begin to curl into a ‘C’ shape before pupating. The pupae will get dark and after 2-3 weeks will hatch out into adult beetles. Once the beetle has emerged it can live up to half a year. It may take a few weeks for the beetles to start producing eggs and the cycle begin again.

10. Are superworms found in the wild in Australia?

Superworms are not found in the wild in Australia. Instead, they are bred and imported to Australia most commonly as pet food for species like reptiles. They are native to Central and South America where they spend most of their time decaying vegetation, leaves and tree bark.

They pupate in the soil then as the beetle emerges its diet will remain very much the same as it was when it was at the larvae stage. Darkling beetles continue to live in the soil and are active day and night. They prefer cool, damp places and when hot prefer dark and damp conditions.

Superworms are very nutritious and are a healthy and valuable source of protein. In Australia, they are raised on farms and are fed on oatmeal, whole wheat bread, greens and other vegetables and can be consumed by humans.

It will be remained to be seen if indeed the plastic-eating superworms will be fit for human consumption!